Louis Fratino’s new exhibition “La scorza” at Galerie Neu in Berlin reimagines tenderness and touch through bronze and terracotta, exploring the male form with reverence, intimacy, and sculptural depth.

The New York-based artist extends his figurative lexicon into bronze and terracotta, offering a tactile treatise on masculinity, intimacy, and the historic weight of materials. Fratino, long celebrated for his painterly handling of the male form and his tender depictions of domesticity, now brings these themes into sculptural relief—literally and metaphorically. The show’s title, taken from a Sandro Penna poem, translates to “the rind” or “the skin,” a fitting entry point for a body of work that luxuriates in surface and sensation.

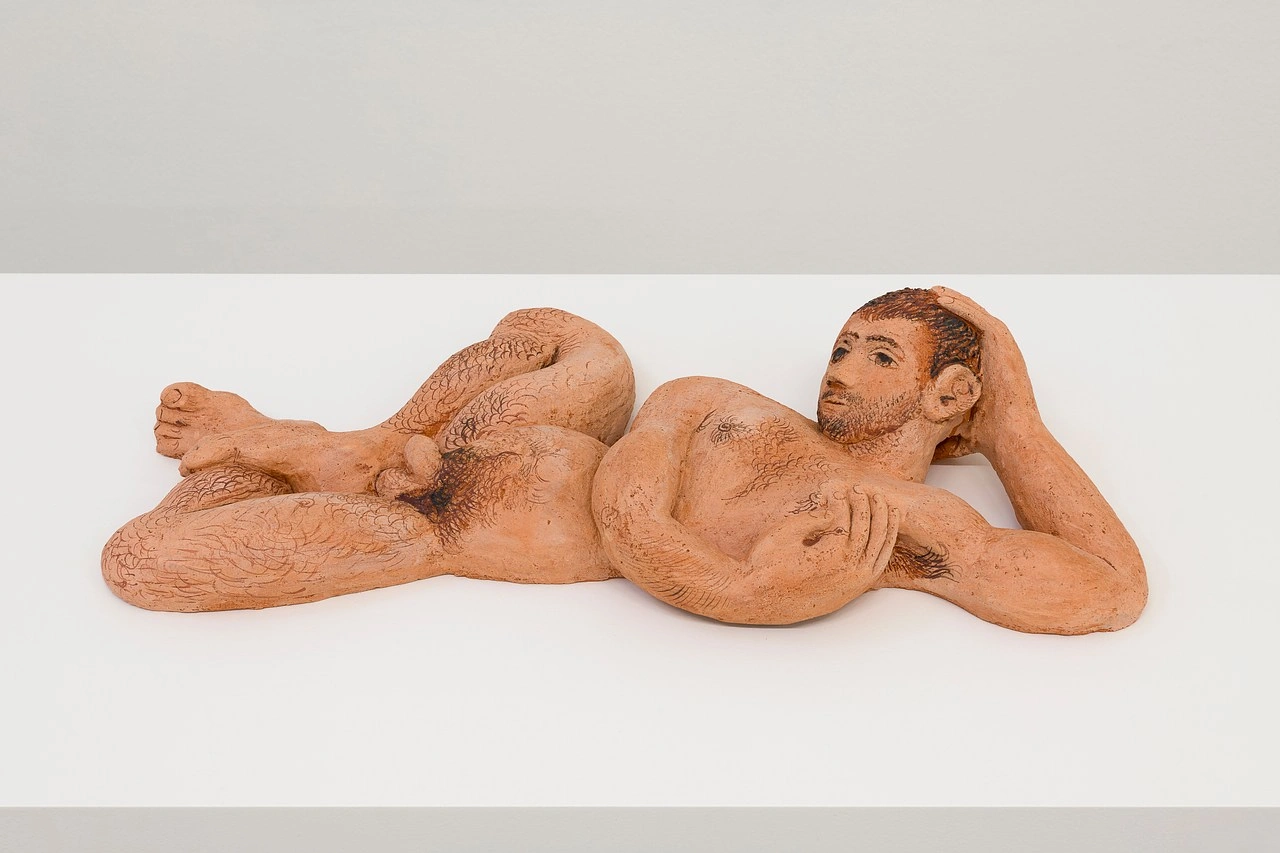

“La scorza” foregrounds the tensions between strength and sweetness, muscle and memory. Fratino’s new bronze sculptures and terracotta bas-reliefs do not so much monumentalize the male body as they soften it. Limbs curl, torsos twist, but always in gestures of rest or reverie. There’s no heroic posturing here—only vulnerability cast in solid form. This is a sculptural language rooted in touch, one that disarms with its intimacy. Even at their most classical in proportion, these figures seem sculpted less by chisel than by affection.

The poetic companion to the exhibition, “La Vita Morta” by Jahan Khajavi, sets the emotional register: angels appear in the form of wrestlers, marble bodies are kissed cold, and desire flits between the living and the statuary. In concert with Fratino’s sculptures, the text offers not just context but resonance—a kind of metaphysical echo. Both artist and poet explore the divine in the domestic, and the erotic in the elegiac.

Fratino’s sculptural materiality also echoes his time in Albissola, Italy—a region saturated with ceramic tradition. While his earlier forays into terracotta began during this 2019 residency, “La scorza” marks the debut of his bronze works. Bronze, with its weight and history, might seem a departure—but in Fratino’s hands, it retains a sense of warmth. These are not monumental bronzes in the conventional sense; they are contemplative, almost private. A bronze arm, draped over an invisible bed. A terracotta torso, its surface dimpled like wet clay just touched.

What makes Fratino’s work particularly compelling in this show is its commitment to embodiment—not merely representing bodies, but making the viewer feel as though they’re encountering them. There’s a palpable sensuality in these surfaces, one that turns the gallery into a site of quiet intimacy. You don’t just look at these sculptures—you imagine holding them, tracing them, loving them.