Christelle Oyiri’s Heaven’s worth, Hell on earth, at Galerie Buchholz in Berlin, presents a terrain of longing built at the intersection of memory, desire, and spiritual rupture.

Oyiri doesn’t simply juxtapose paradise and torment—she collapses them into one field, digging where faith, colonial histories, and diasporic imaginaries breach the sacred and the profane.

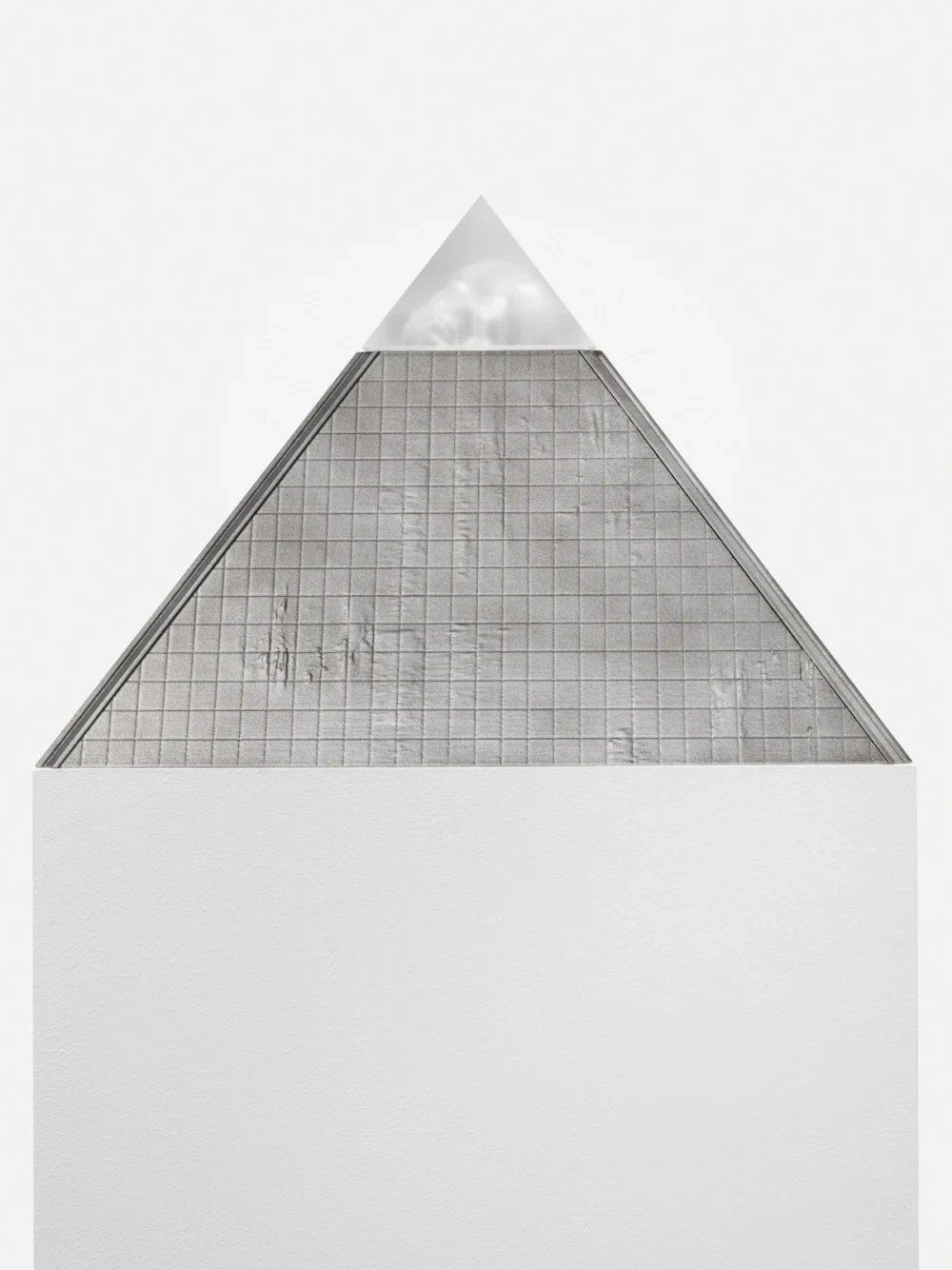

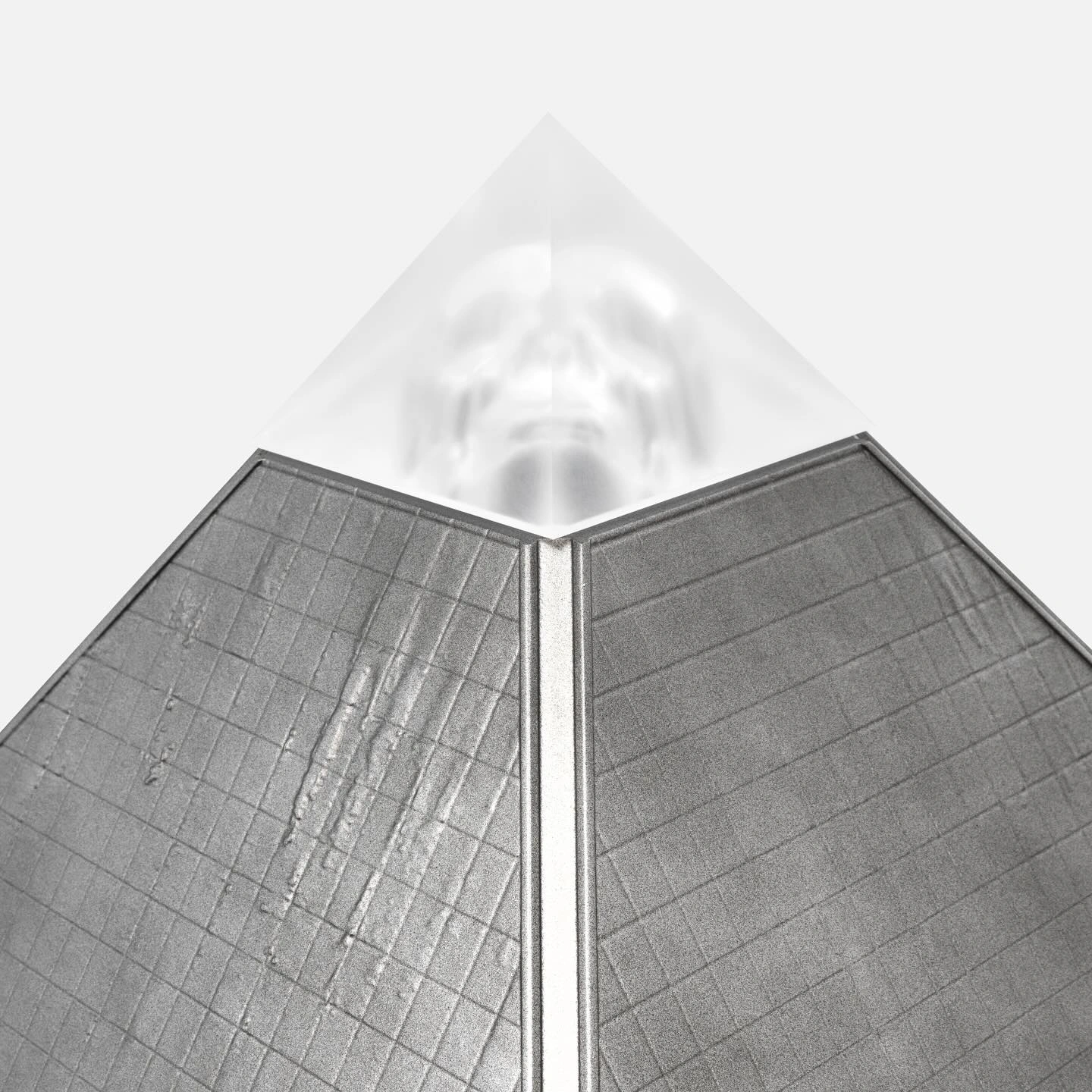

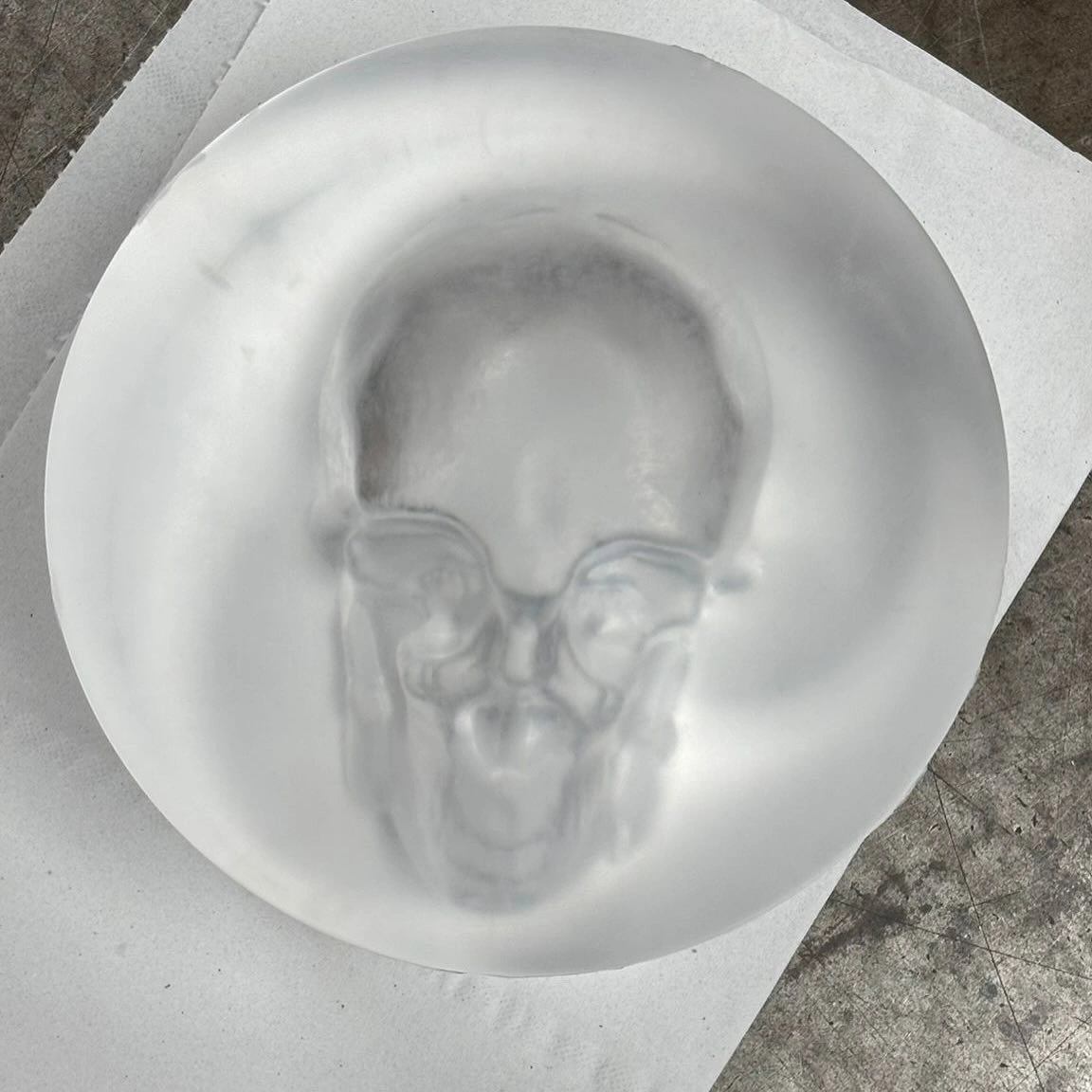

From the outset, Oyiri’s language—and her chosen materials—signal a tension between what is wrought and what is inherited. Imagery of crucifixes, prayers, reflection, recording tape, static, aluminum, monuments: these are not just symbols but anchors for histories that refuse silencing. Oyiri’s reference to “Kemet, dreamt in aluminum / a monument half‑remembered, half‑invented” suggests a reclamation of Egyptian antiquity—not as fixed heritage, but as mutable myth, glossed and refracted through displacement and transformation.

Metal becomes both archive and weight. Memories cast in metal are “heavy”; holiness is inseparable from sacrifice or transgression. Oyiri seems fascinated by survival: what persists when the material body fails, when empires erase, when belonging is contested. Her use of sound, object‑sculpture, and installation create immersive thresholds rather than distances, inviting the viewer to dwell in unease, to consider what is mirrored back when desire stretches “across every surface.”

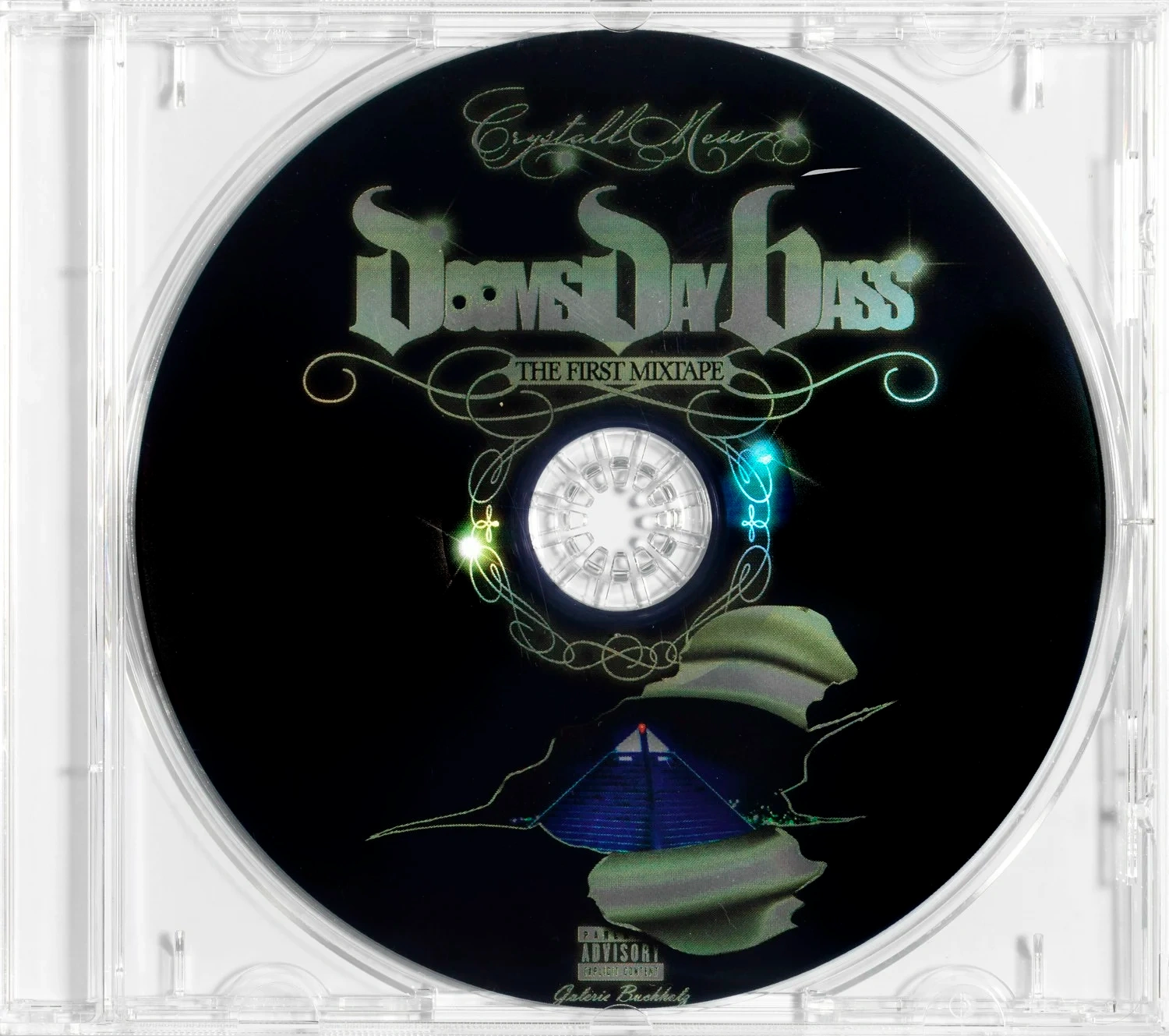

The exhibition’s sonic dimension further complicates its physicality: Oyiri’s mixtape DOOMSDAY BASS is part of the display, a signed tape on CD with long duration, housed in vintage devices – for instance a Bang & Olufsen Beosound Ouverture. Sound here is not background but architecture: it reverberates with the past, with decay and promise. It becomes a companion to the visual: distortion, hiss, static, signals, all those margins where meaning frays.

In Berlin, Oyiri’s work feels urgent—not only for its aesthetic intensity but for what it stages: the interplay of colonial extraction, Black diasporic spiritualities, personal mythologies, and the legacy of restriction imposed by religion. Paradise, she insists, is never pristine; it is always built under threat, always haunted by what lies just outside the frame. And hell, as she shows, is woven into the everyday.

Oyiri asks: how do we honour the weight of what we carry, when those weights are forged in oppression, when holiness demands transgression? Her paradise and purgatory live side by side, and in their friction she locates a kind of fidelity—not to innocence, but to truth.