Among plum trees in suburban Tokyo, Kazuyo Sejima compresses a family home into a steel prism where light and rooms interlock, windows cut like paintings, and life slides between house sky and garden.

On a corner plot in Tokyo’s Setagaya district, a small grove of plum trees sets the brief. Rather than clearing the site, Kazuyo Sejima threads a home around their trunks, treating the trees as existing citizens of the neighbourhood. The house is not an object dropped into a garden but a vertical clearing within it, a slim prism that rises between branches and fences, letting the foliage remain the first thing you notice from the street.

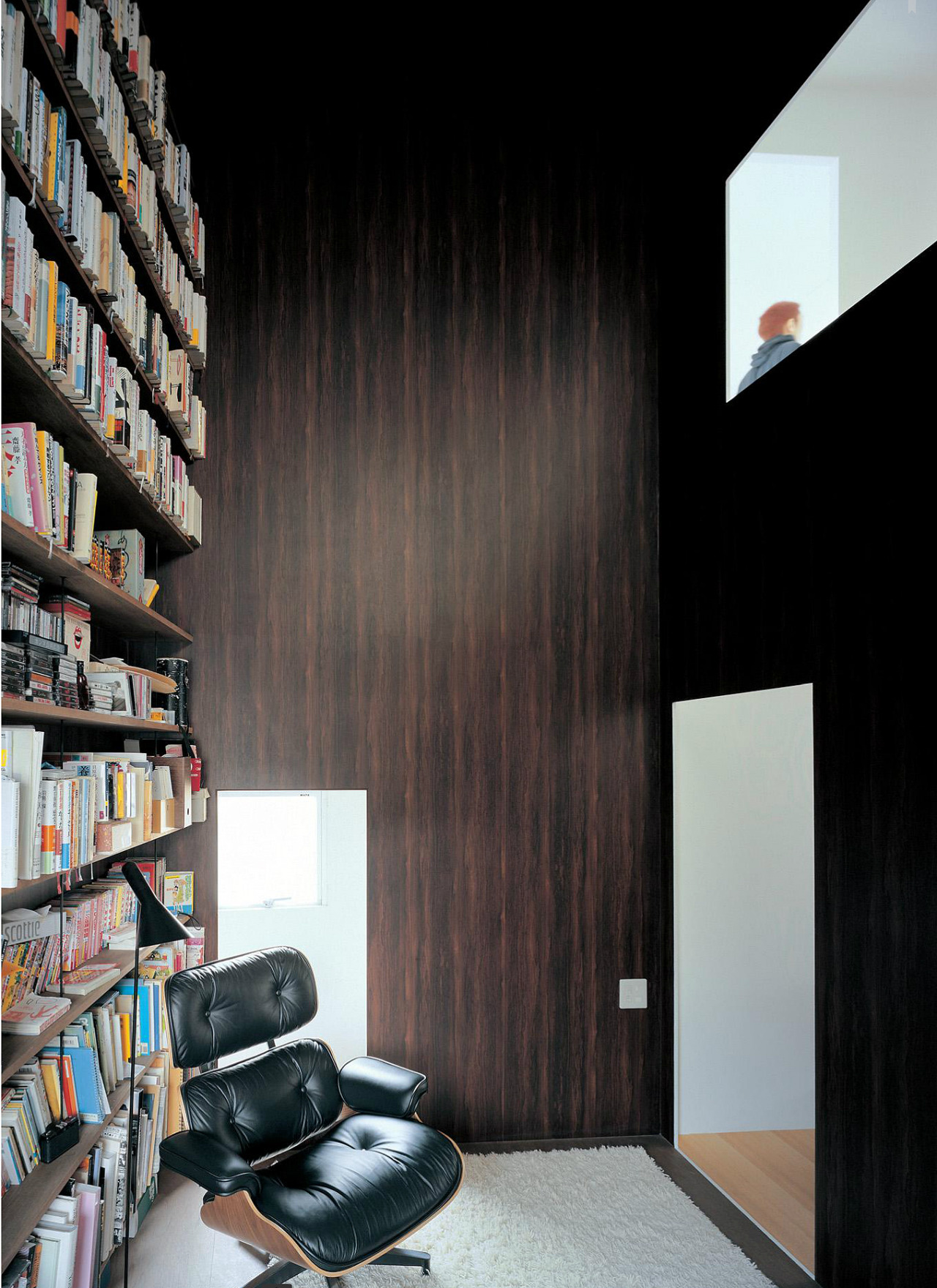

To keep as much ground free as possible, the building contracts into a triple-height steel volume with a trapezoidal plan placed at the centre of the plot. Inside this compact shell, the usual domestic hierarchy dissolves. Seventeen rooms of different sizes – for cooking, reading, working, bathing, sleeping – are stacked and stitched together, not by corridors but by a loose continuity of levels and openings. The spaces belong less to individual family members than to the activities that pass through them.

As you move up through the house, the sequence shifts from shared to intimate. On the ground floor, the entrance, kitchen, dining space, tatami room and bathroom occupy the four broad corners of the plan, held in a quiet balance around the garden. Higher up, a small library and bedrooms with adjacent workspaces gather in the middle of the section, suspended between street and sky. At the top, a bathroom and a tiny tea room open towards the roof terrace, turning the highest point of the house into a place of slow, solitary rituals.

A narrow spiral stair coils through the structure like a piece of inhabitable furniture, slipping between the four main walls and touching each landing almost casually. Those walls are made from slender welded steel plates, only a few centimetres thick. Because they are so fine, they can be cut and folded with precision, carrying both structure and partition while occupying almost no space. The result is a shell that feels at once weightless and robust, a frame for daily life rather than a heavy enclosure.

Openings are scattered across these white planes in a range of sizes, from shoulder-height slits to large, almost square cuts. They act less like conventional windows and more like frameless pictures hung in the walls: views of a child’s desk from the stair, of a neighbour’s façade beyond the trees, of branches brushing against the glass on a windy day. These sightlines connect the seventeen rooms without erasing their privacy, and they stitch the interior back to the plum grove outside. Over time, as the trees thicken and the seasons turn, the house becomes a subtle instrument for watching the garden change, holding a family and a small piece of Tokyo in a single, continuous space.