In Paris, Precious Okoyomon conjures a dreamlike apocalypse where erotic bears and atomic intimacy unravel the logic of shame through fables of care, collapse, and cosmic relation.

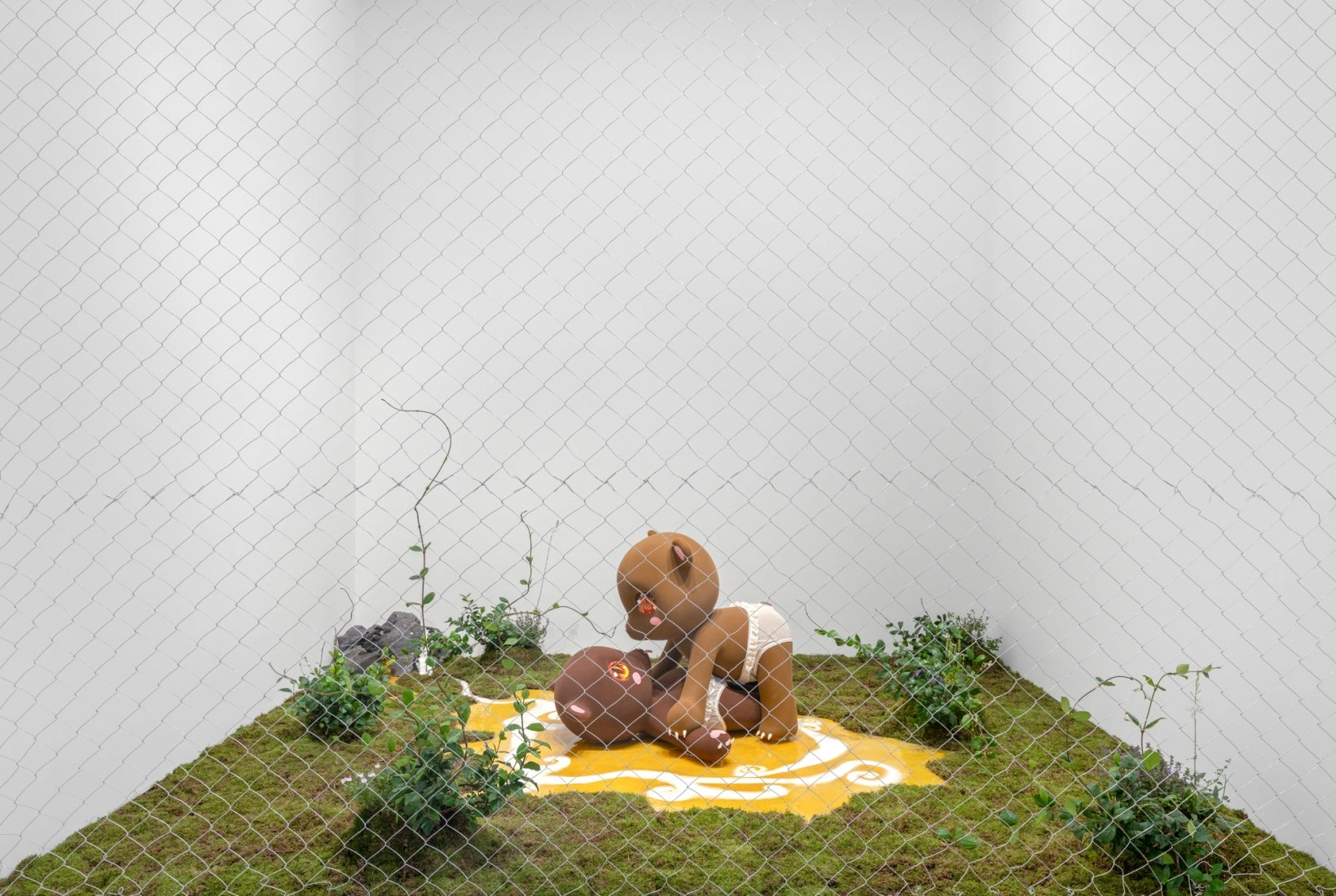

At Mendes Wood DM in Paris, Precious Okoyomon has staged something like a fable spun through the digestive tract of an angel on ecstasy. Titled “It’s important to have ur fangs out at the end of the world,” the show is an ecosystemal fever dream—fragile, libidinal, mischievous. Okoyomon, known for summoning post-apocalyptic gardens and living installations, leans deeper into the erotics of care and the metaphysics of relation. The work is not narrative but operatic—a myth told through dioramas, drawings, wallpaper, and those uncanny, ever-watching bears.

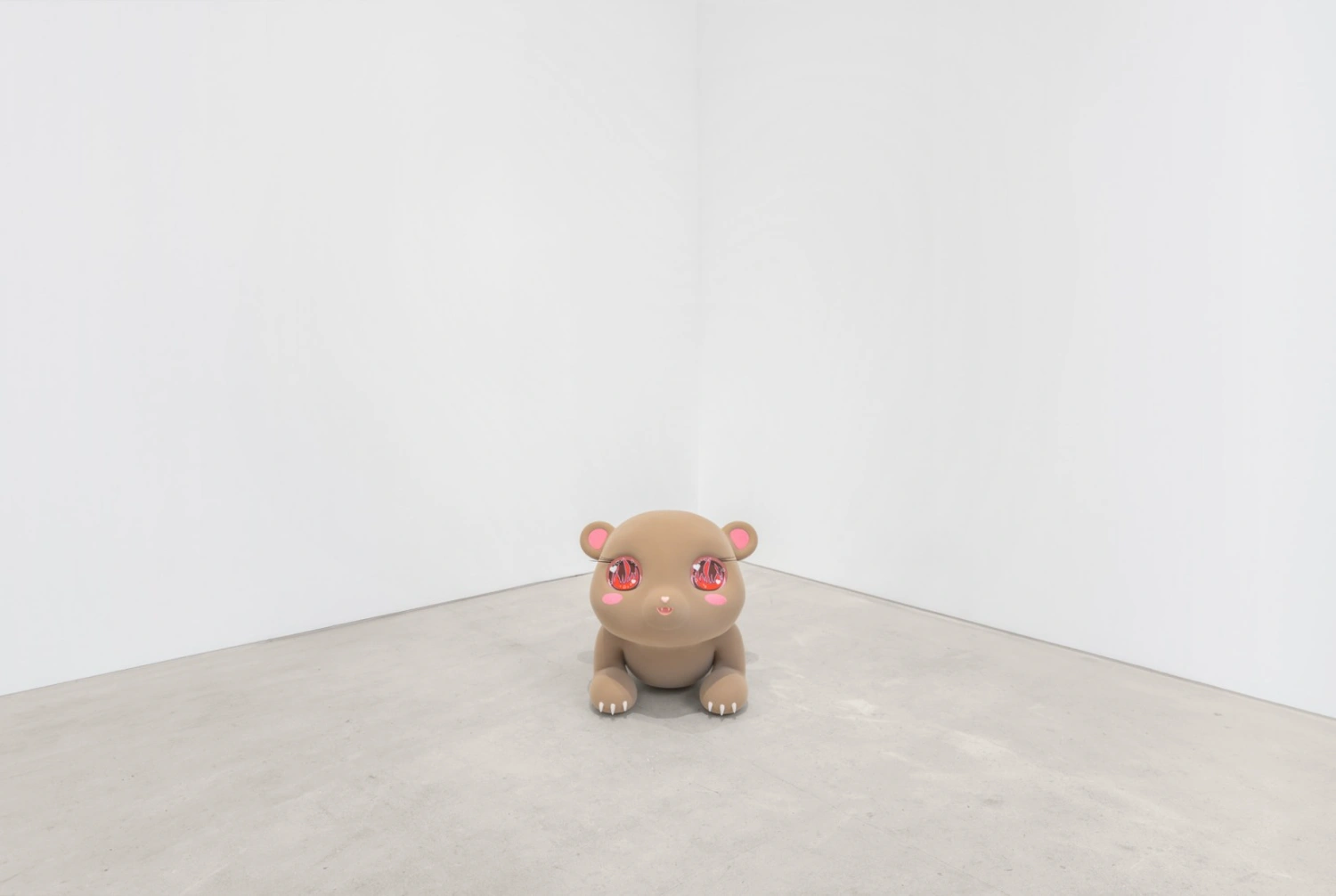

These bears—plush, exposed, sexually ambiguous—anchor the space like strange deities of a playground cult. Their rounded bellies, lace panties, and shimmery eyes exude a perverse innocence, a softened affront to shame and repression. Protected behind glass or nets, they inhabit their own closed loop of pleasure. Like transitional objects, they oscillate between the infantile and the sacred, metaphors for a relational self that is always incomplete, always in becoming. Here, Okoyomon doesn't offer critique so much as seduction—drawing us into a world where softness is armor and exposure is ritual.

At the atomic level, the show hums with the logic of physics: nothing exists alone. Like Sloterdijk’s microspheres, or particles vibrating in fields of force, every form and gesture here exists in relation—to another, to nature, to memory. Even the drawings, some scorched with fire, evoke the entropy of systems that are alive, vulnerable, interdependent. The apocalypse in Okoyomon’s lexicon is not a singular event but a mode of being—ecstatic, porous, unresolved. “The I is always plural,” the exhibition seems to whisper.

Eroticism here is not merely sexual but structural—a way of refusing fixed identities or moral hierarchies. The bears’ open postures, their anointed orifices and fecund gestures, embrace a cosmology of touch that resists cleanliness or closure. There is no binary between care and carnality, no difference between milk and decay. Love, as Christina Sharpe suggests, is not redemptive but method: a movement through and with brokenness, a refusal to let pain petrify.

Okoyomon’s ecological references are not benign pastoralism but feral systematics—overgrown, tangled, voracious. Gardens and beings alike devour as they nurture. This is fragilization as method: the embrace of what Ettinger calls the “matrixial borderspace,” where empathy emerges not through strength but through penetrability. It’s a politics of emotional mycelium—trauma metabolized communally, through pleasure as much as grief.

What remains is a world seen from a particle’s vantage: borderless, circling, already ending and endlessly beginning. The show is apocalyptic only in the sense that it marks a transition—a letting go, a glimmering fall into the intimacy of everything. Okoyomon’s fable doesn’t warn us of the end but invites us to bite into it, fangs bared, mouth full.