In The Garden, now showing at Hannah Barry Gallery in London, Harley Weir transforms personal memory, tactile experimentation and feminist longing into a radically intimate visual terrain.

Known for the aching tactility of her images, Weir crafts a space where personal mythology collides with feminist futurity. Here, nostalgia is neither sentimental nor resolved—it churns, ferments, and destabilizes. The Garden becomes not only a title, but a framework, a cosmology of beginnings and endings, where fertility, decay, and desire coexist in unflinching proximity.

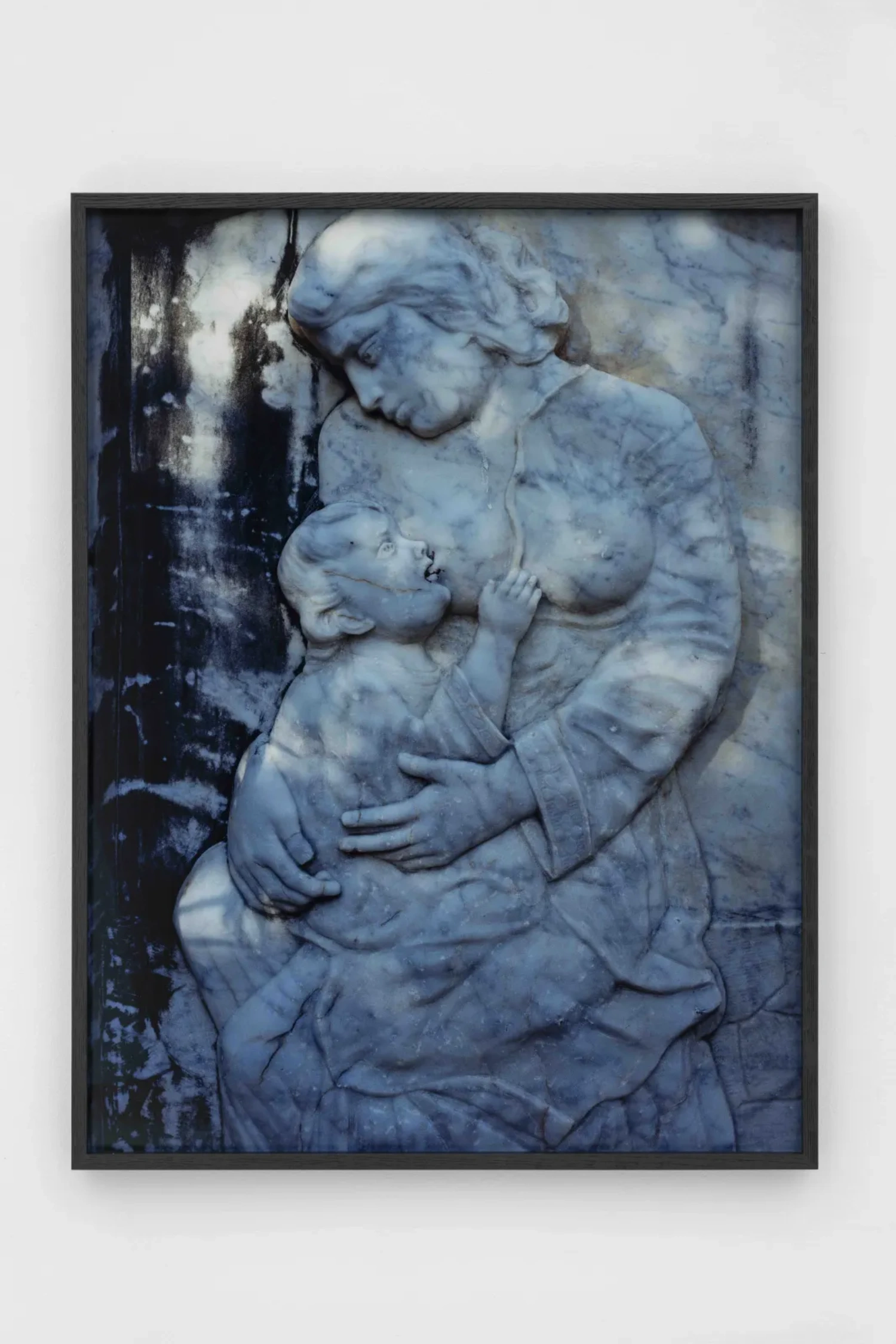

Downstairs, Weir leads us into the terrain of adulthood, one marked by the slow passage of time and the intimate rituals of care. The imagery is raw, sometimes somber, but always precise—a visual diary of womanhood rendered through a lens that is both brutal and tender. Her ongoing dialogue with maternal lineage and bodily autonomy surfaces in layered compositions that echo psychoanalytic tropes while staying rooted in the tactile: skin, time, blood.

Upstairs, the mood shifts—adolescence is rendered in soft, sugar pastels, though the sweetness never feels naïve. Weir memorializes her younger self through the alchemy of handmade paper embedded with butterfly wings, dried petals, and teenage ephemera. These artifacts, once trivial, now possess a strange, almost sacred aura. By merging photography with the physical residues of memory, Weir collapses the distance between archive and artwork, body and image.

The exhibition’s Sickos series extends her darkroom experiments—where blood, vitamins, and hormones disrupt photographic chemistry to yield images that are haunting and insurgent. What emerges is not destruction, but transfiguration. In Weir’s hands, the body is never fixed—it is mutable, porous, susceptible to light, time, and transformation.

With The Garden, Weir offers a radical grammar for the contemporary gaze—one rooted in emotion but charged with critique. She continues to navigate the intersections of beauty, activism, and the grotesque, reminding us that photography, at its most vital, can be a site of both rupture and repair.