Prada Aoyama Glass Tower by Herzog & de Meuron compresses a retail program into a crystalline vertical figure in Tokyo’s Aoyama district, exchanging building footprint for urban generosity.

Most luxury flagships claim as much ground as the site will allow. Herzog & de Meuron did the opposite. On a 953-square-metre parcel in Aoyama, they compressed 2,860 square metres of Prada’s retail programme into a compact vertical figure and released nearly two-thirds of the lot as open plaza. The arithmetic is striking: the building occupies a 369-square-metre footprint, and everything else is given back to the street. In a district defined by commercial density, this reads less like generosity than like strategy — the understanding that in a tight urban corridor, a void is more memorable than a mass.

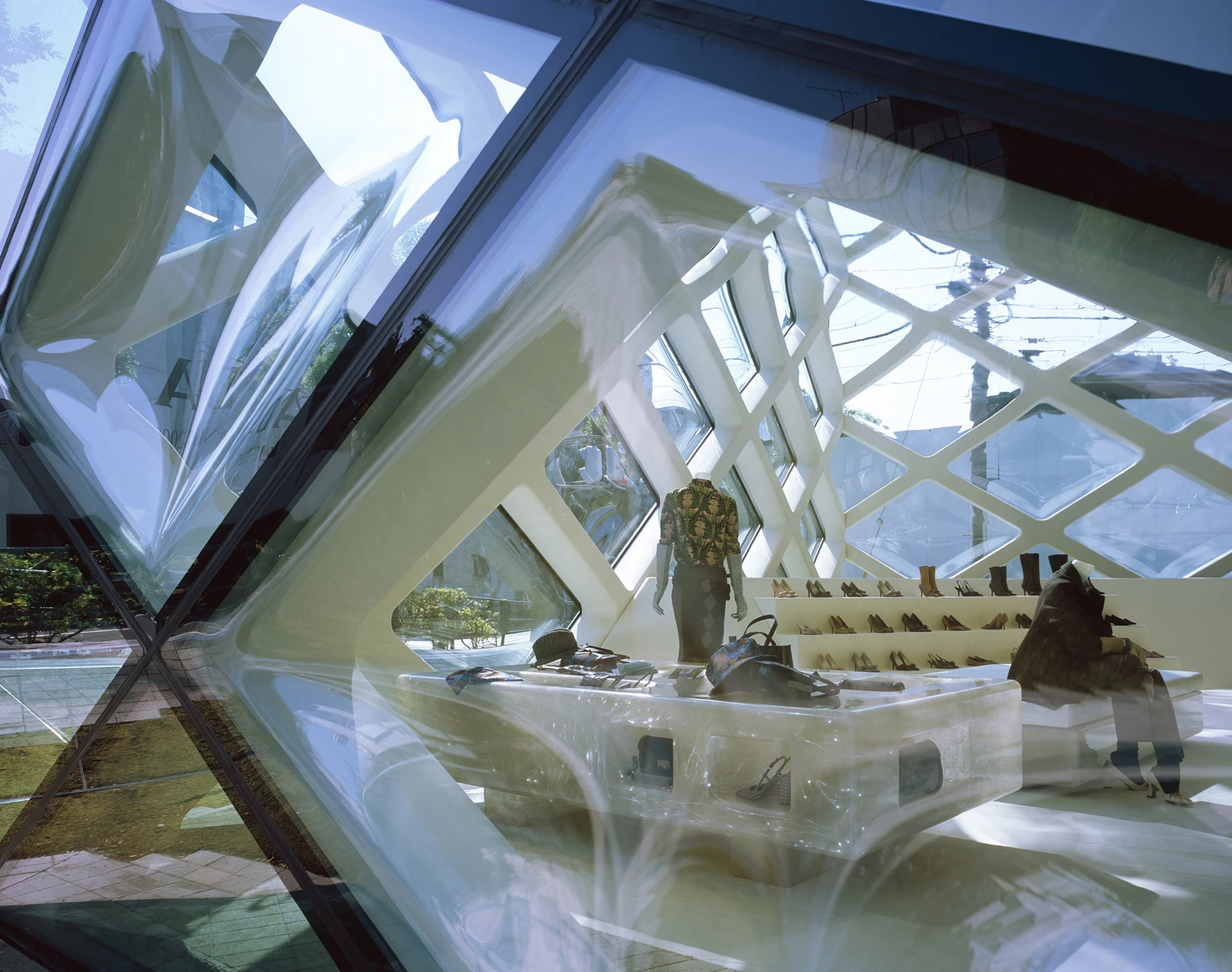

The tower’s silhouette follows the angles prescribed by local building code, yielding a chamfered volume that oscillates between crystalline object and saddle-roofed archetype depending on where you stand. A rhomboid diagrid wraps the facade and is infilled with convex, concave, and flat glass panels — each curvature acting as a lens that compresses and expands fragments of the city at different scales. The building never looks the same twice. Morning light turns it translucent; at dusk it reflects the street back onto itself in distorted loops. This is not a skin applied over structure. The diagrid is the structure, working with the vertical cores to support floor slabs at the perimeter, eliminating the need for a separate frame.

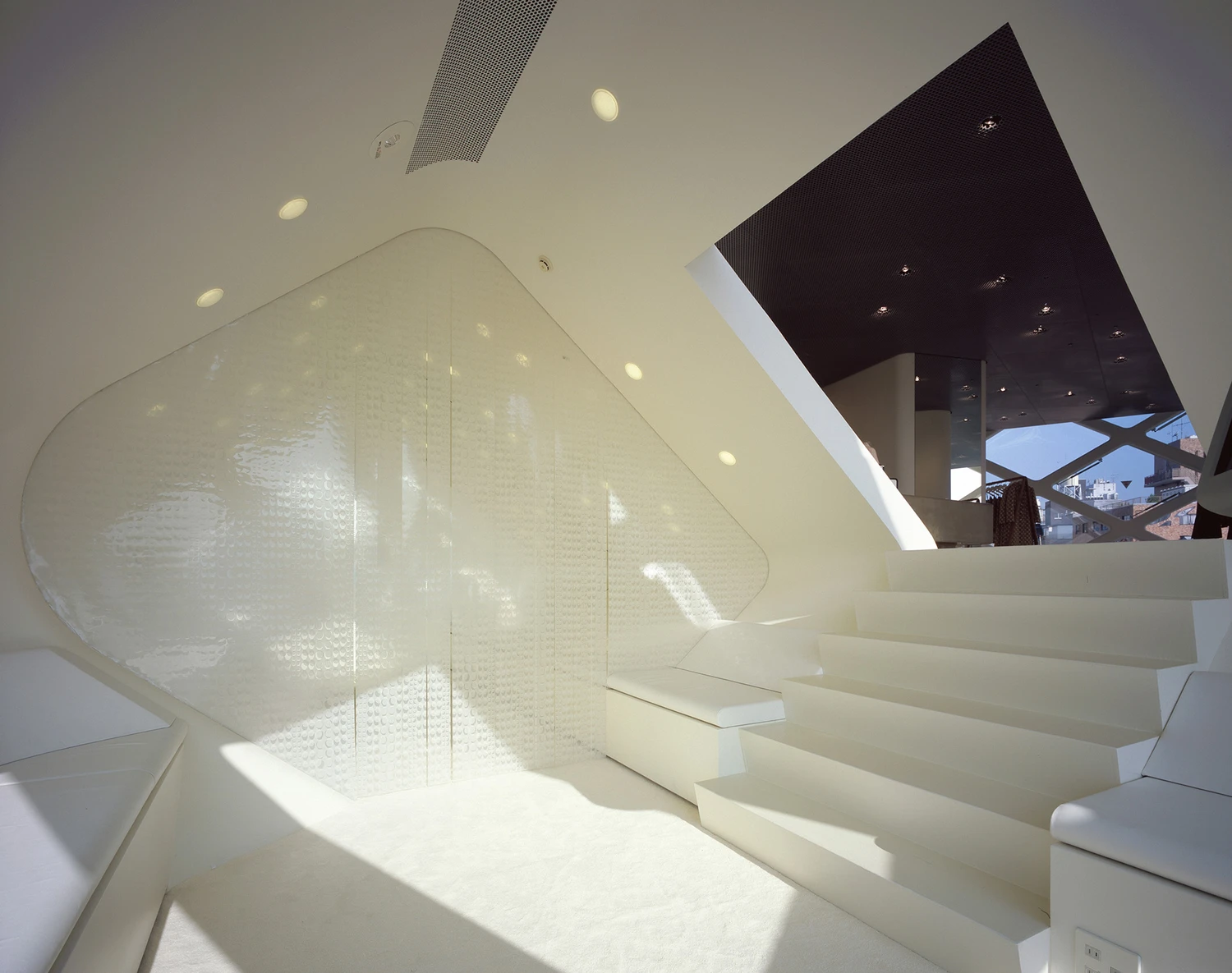

Inside, horizontal tubes span between the cores, simultaneously stiffening the structural shell and housing programme: changing rooms, counters, services. The floors read as open platforms interrupted by these inhabitable cabinets, maintaining sightlines across levels and toward the city while allowing pockets of privacy within a fundamentally transparent envelope. The diamond modules of the facade align precisely with the tube positions, so the structural logic of the exterior becomes the spatial logic of the interior. One system, expressed twice.

The material palette resists easy characterisation. Hyper-artificial surfaces — resin, silicone, fiberglass — sit alongside hyper-natural ones: leather, moss, porous timber. The juxtaposition is not eclectic but deliberate, placing craft and industrial fabrication within the same optical and structural matrix. Custom furnishings and lighting were conceived as extensions of the architecture itself, calibrating reflectivity and tactility to negotiate the competing demands of display, circulation, and intimacy.

More than two decades later, the building still holds. Not because it shouts — Aoyama has plenty of that — but because it demonstrates something quietly radical: that constraint, read correctly, produces not limitation but spatial intelligence. The plaza remains one of the most generous public gestures in the district. The facade still catches you off guard. The interior still makes you look up through floors you didn’t expect to be able to see through. It is a building that solved its problems so cleanly that the solutions became invisible, which is the hardest thing architecture can do.