Maputo Diary by Ditte Haarløv Johnsen spans 1997 to 2022—a quarter-century of photographs documenting the transgender and queer community of Mozambique's capital.

Ditte Haarløv Johnsen grew up in Maputo during the years following Mozambican independence, when the country was rebuilding itself after colonial rule and civil war. Her childhood there planted something that would only flower later: a sense of belonging to a place that was not, by conventional measure, hers to claim. When she returned as an adult with a camera, the work that emerged would span twenty-five years and several lifetimes.

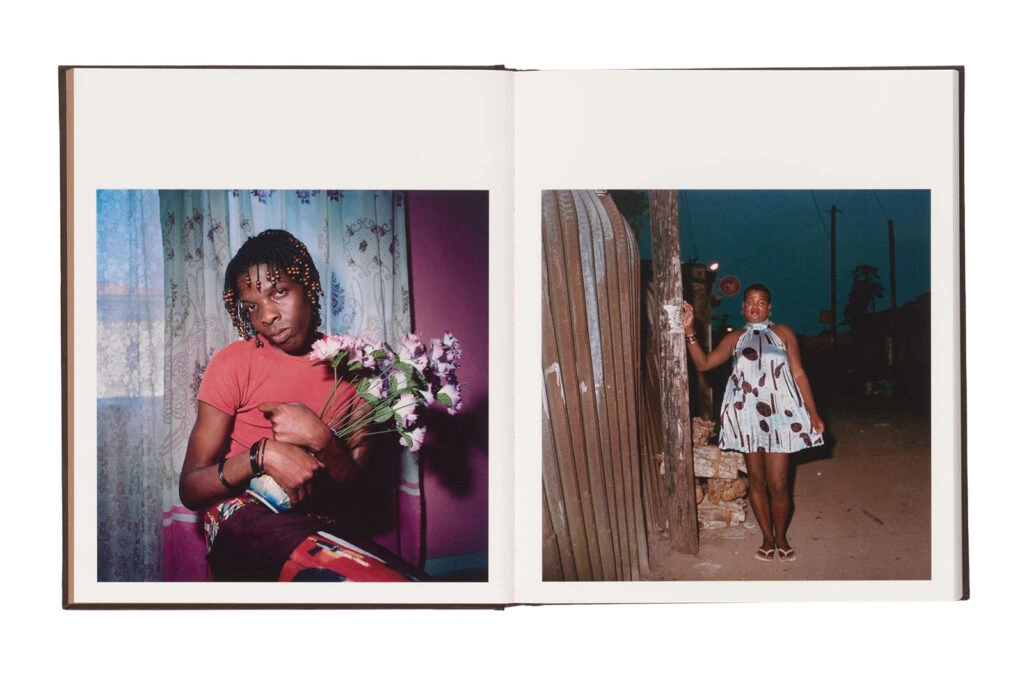

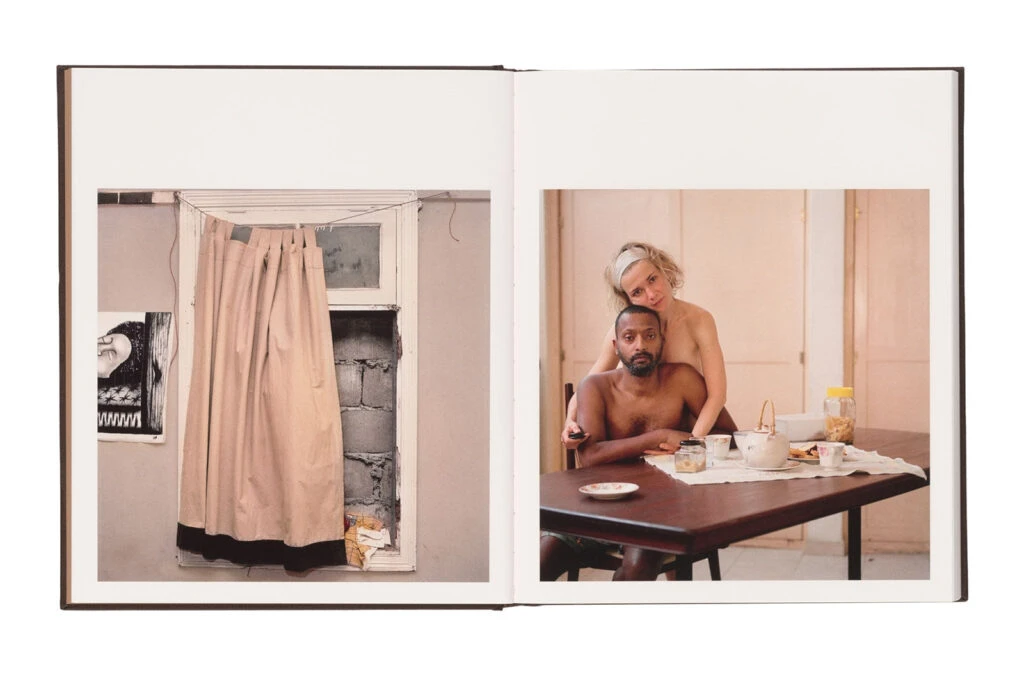

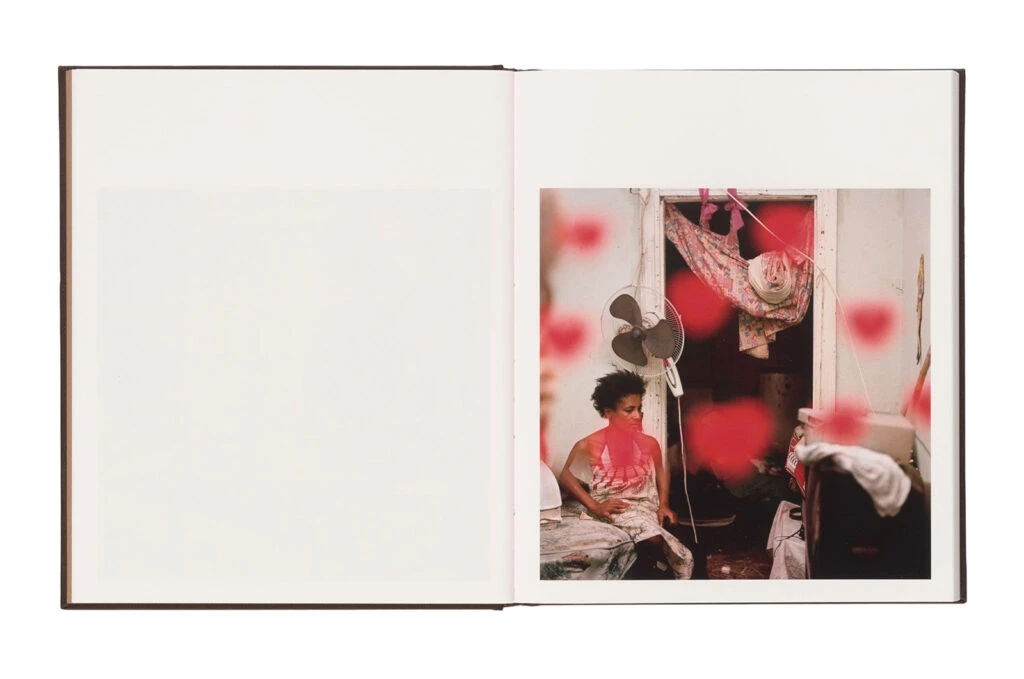

The book centers on three protagonists—Ingracia, Yara, and Antonieta—trans women whose lives Johnsen documented with an intimacy that only long friendship permits. These are not portraits taken during brief encounters but images accumulated across decades, showing bodies and faces transformed by time, circumstance, and the particular courage required to live visibly in a society that often preferred invisibility.

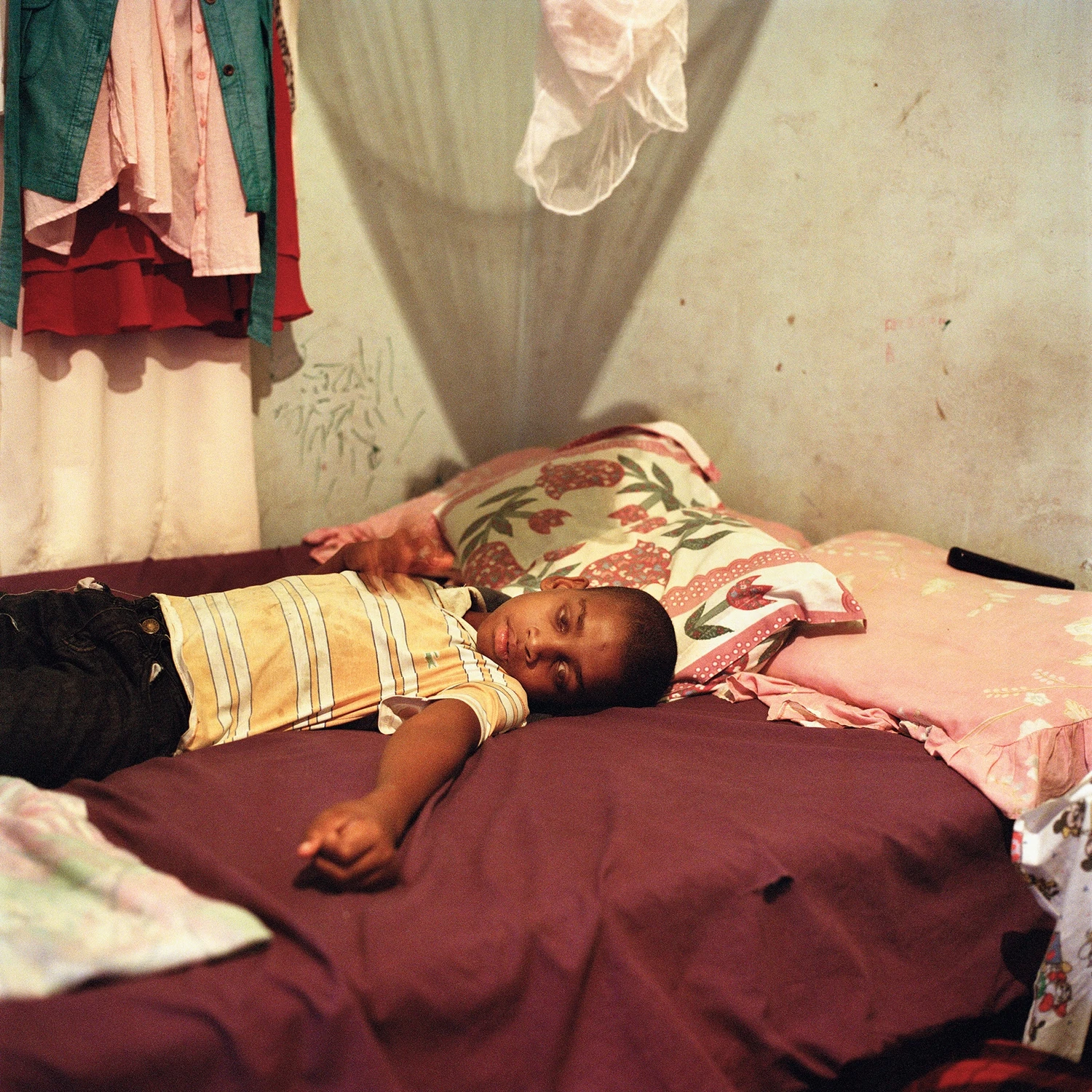

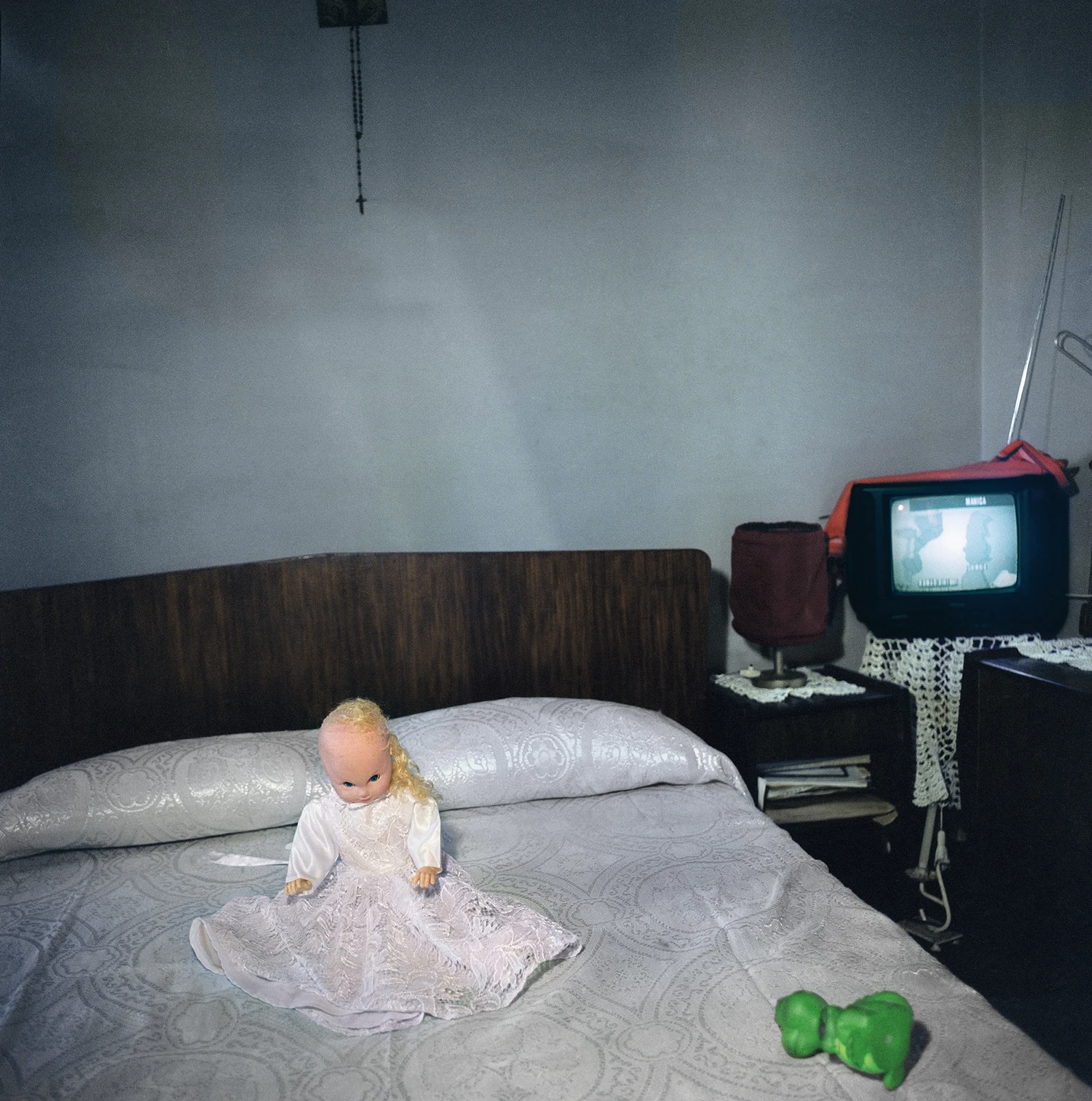

The photographs move between registers: domestic interiors where subjects arrange themselves for the camera, night scenes where the city's darkness offers both danger and freedom, moments of tenderness between friends that carry the weight of survival. Johnsen's approach refuses both exploitation and idealization; her subjects appear as fully human, which is to say complicated, contradictory, beautiful, and weary by turns.

Published by Disko Bay, the book confronts questions that documentary photography often elides. Who has the right to tell whose story? What obligations persist across years and continents? Johnsen addresses these directly in her text, acknowledging the privileges that allowed her access while honoring the trust that sustained it. The work becomes an argument for long-form engagement—for the kind of seeing that only time permits.

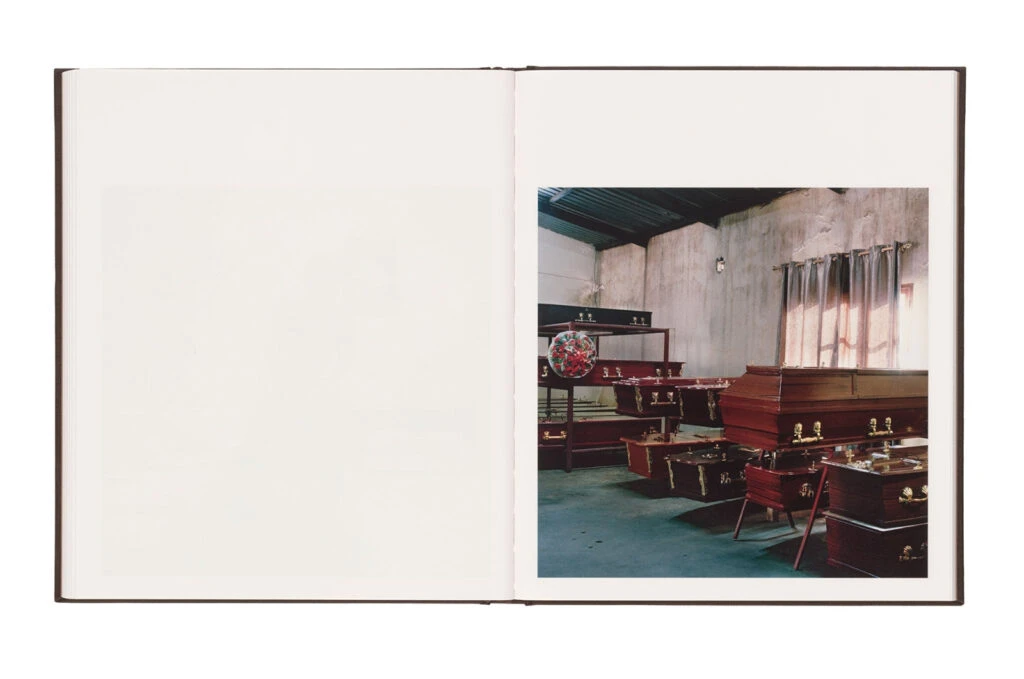

Maputo Diary operates as archive and elegy simultaneously. Some of its subjects have died; all have aged. The community itself has changed as Mozambique has changed, its contours shifting with legal reform and social pressure. What the photographs preserve is not a fixed state but a relationship—between photographer and subject, between a city and those who make it home against considerable odds.